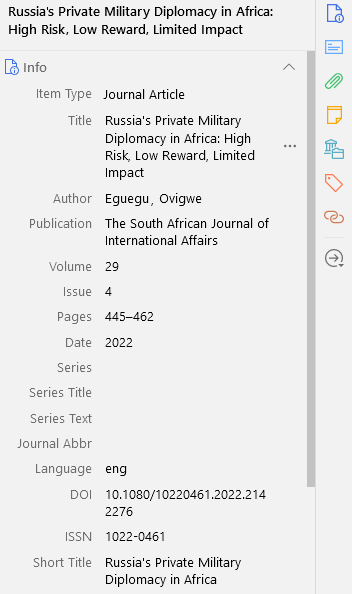

Zotero is probably the most exciting bit of software this program has thus far introduced me to. I began by creating a History and a Political Science collection in the library to split the works I would be collecting between my two primary fields.

Once the core categories were set up, I started populating them with literature on violence by non-state actors, my chosen subject of study in both Political Science and History. At this stage, I was still separating them out into the same two categories.

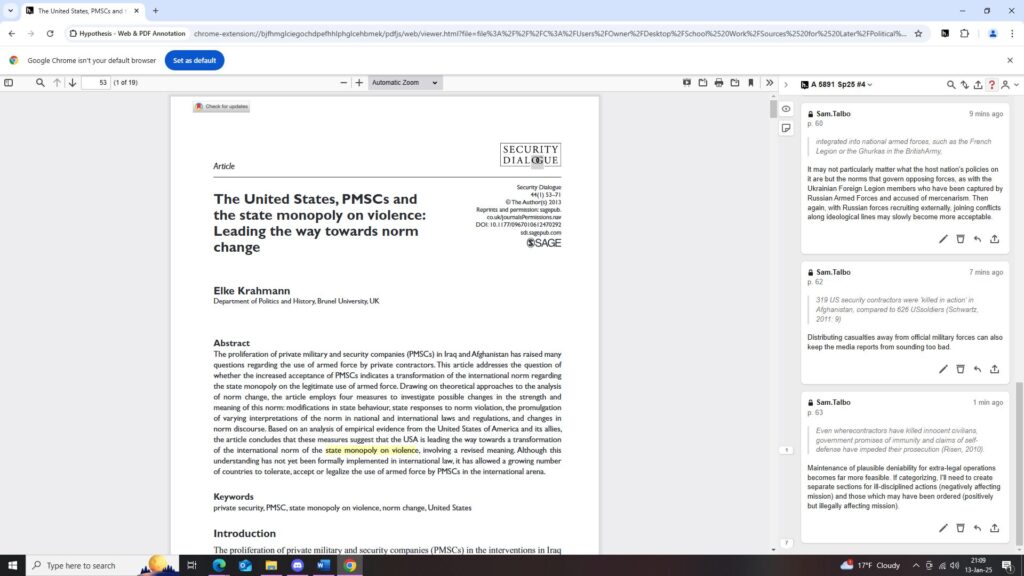

Throughout this process, I was expecting to need to intervene in the citations Zotero was providing, but I never experienced any issues. The software seems to be reading WMU’s library website perfectly and the one article I took from another cite (a dissertation from Murray State) seems to have loaded correctly as well, missing only the abstract. The one issue which appeared consistently was the capitalization in article and journal titles; notably, this was the WMU Library’s fault rather than the software’s. Helpfully, Zotero had a tool for this, allowing me to set any field to “Title Case,” automatically capitalizing items in that field.

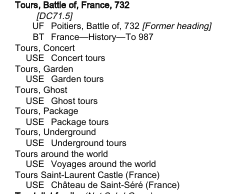

The auto-generated tags were unfortunately not the most useful items. They were too numerous and too specific to be helpful. For example, having added four articles on the topic of Chechnya, the tag “Chechnya” brought up only two of them and the tag “Chechen” brought up only one. Still, the tag system itself seems useful once I delete the existing items and add my own.

Once my initial twenty-five items were set up, I started to look towards creating subcategories. I mainly wanted to separate out History titles dealing with Late Antiquity (my specialty) from a handful of other titles I had collected.

Once this was done, my library was effectively complete for my purposes, although I’m certain more subcategories will need to be set up as I progress through new projects. Thus far, I’m deeply impressed with this software. Zotero has delivered citations practically ready for use with every book and article which I tracked down.